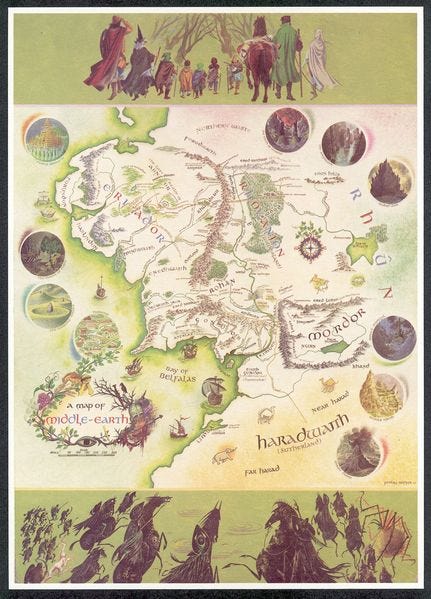

The best fantasy map ever

Listen, sitting under a tree sounds great

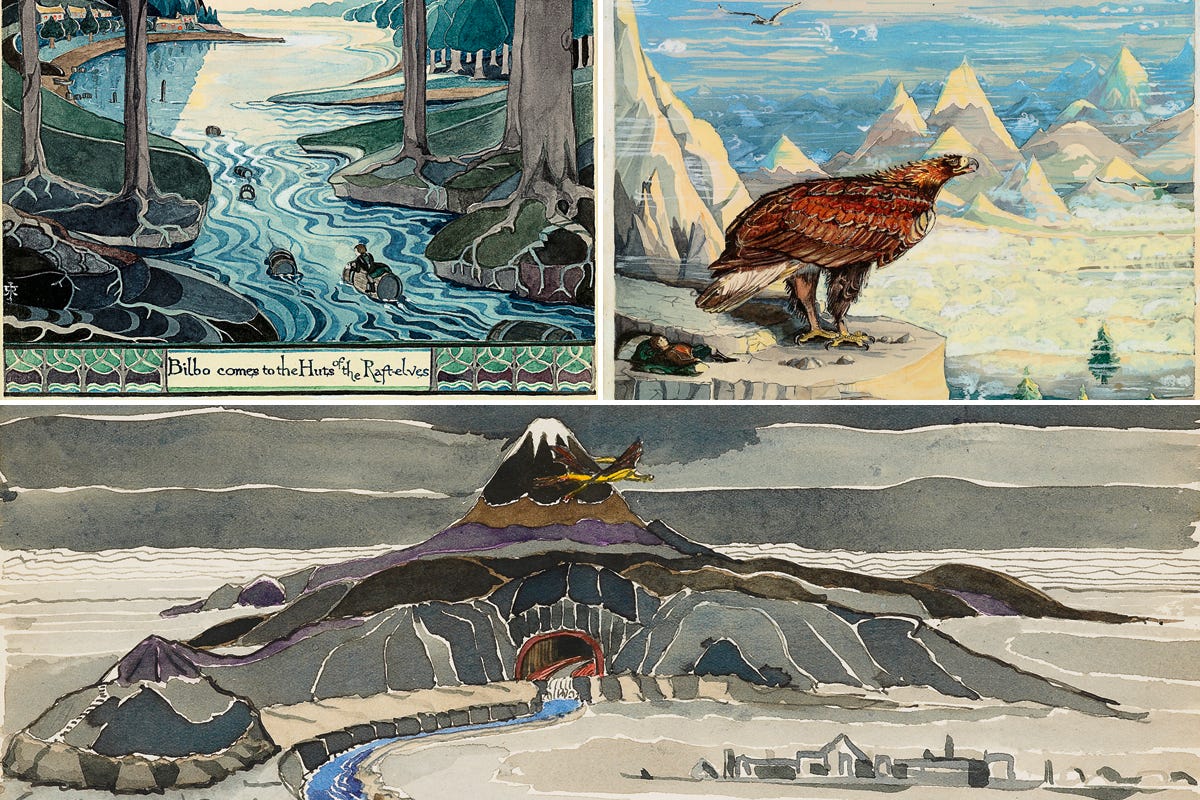

How the illustrations in The Hobbit explain why D&D is all about fighting

Why do fantasy books need maps?

To be certain, they have plenty of maps. It has become de rigueur for almost every new fantasy novel published to have a map. And that isn’t universally loved.

Some people have complaints about the actual contents of fantasy maps. Professional cartographers or geologists like to whine about the geological impossibility of some of the fantasy worlds. For example, there’s this essay about the reasons that Middle Earth’s mountain ranges make no sense. https://www.tor.com/2017/08/01/tolkiens-map-and-the-messed-up-mountains-of-middle-earth/

But there is also some pushback about the entire concept. The author N. K. Jemisin, best known for the acclaimed Broken Earth series, has stated that she’s no fan of fantasy maps, as in this interview http://fantasybookcritic.blogspot.com/2010/04/interview-with-nk-jemisin-interview-by.html.

In regards to epic fantasy, as is the want of map to go along, this was missing from your book, any specific reason as to why no map was included?

It wasn't "missing"; I didn't want one. I was reluctantly willing to work with a designer on creating one if that was something Orbit required, in the interests of fitting the standards of the epic fantasy genre -- but fortunately they didn't want a map either, and I was happy with that. Diana Wynne Jones, in her hilarious THE TOUGH GUIDE TO FANTASYLAND, points out that maps have become both a cliché and a kind of spoiler within the epic fantasy genre. The maps in most fantasy novels feature only locations that will become important over the course of the series -- so by looking at the map, any savvy reader can pretty much figure out where the story is going.

(Jemisin has, however, used maps in cases where she’s felt that they are warranted.)

To explain why I love one specific fantasy map, I’ll just take a quick dip into explaining where I find fantasy maps useful.

A wrong turn at Albuquerque

There are clearly some fantasy novels that have maps merely to try to give readers a sense of a larger world, without the novel itself doing any of the lifting.

One book series like that is The Kingkiller Chronicles by Patrick Rothfuss. This competently written pair of novels (I have no idea why these fairly plain books have vociferous fans) have action that takes place in a few locations. In the first book, almost all of the action takes place in one town; the second novel only mildly expands that.

And yet even in the first book, there is a large map of a dozen countries. The map is interesting; it’s more interesting than any of the books so far. But unlike the quote from Diana Wynne Jones above, these maps aren’t spoilers because they have almost no relevance to the books.

There are questions about whether Rothfuss will ever write more books to complete the series. If he does, maybe the maps will matter then. But at the moment, there was no real reason to have them. His novels should either stand on their own or not.

But in many books, the maps do have some real utility. Even with the best author, the verbal descriptions of where the action is taking place can be confusing. A map quickly remedies that.

For example, the main maps in The Lord of the Rings function in that manner. When the Company is arguing, after their failure to cross the Redhorn Pass, about which way they should get past the Misty Mountains, the maps make it clear what their problem is.

In some cases, the maps give the reader the sense that they are traveling along with the group, by making visual references in the book visceral. There is some of that in LOTR, but that is even more blatant in the Earthsea novels by Ursula K. LeGuin, where she often relates the position of the protagonists to nearby sights and landmarks, such as nearby islands. By consulting the map, the reader can understand what the character is seeing.

(That’s something that authors sometimes use even if they don’t include a map in the finished book. For example, in an essay in The Writer's Map: An Atlas of Imaginary Lands, David Mitchell presents the maps he used for his book The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet. No maps are actually in the book, but he sketched maps and plans of a compound to help understand what characters would see and experience as they traversed a specific area.)

Living in the map

In some books, however, the map goes beyond simply giving the reader information. They entice the reader’s imagination to drop straight into the map and live there.

One example of that, for me, is from The Lord of the Rings, but it is not the main map. It’s the smaller map of the Shire, where you can see the various places that Frodo and his friends went in evading the Black Riders while heading out of the Shire—and the places they could have gone but didn’t.

For me, that part of the books is the best. It’s a lighthearted wander in woods and fields that turns into a frantic escape with a nameless horror behind the main characters. It has some of the most beautiful nature writing in LOTR and makes me want to take a walk—and the map shows how my walk might differ from the hobbits.

In a previous newsletter, I quoted several passages from the book that show the travel options in that section of the book. For example:

The sun had gone down red behind the hills at their backs, and evening was coming on before they came back to the road at the end of the long level over which it had run straight for some miles. At that point it bent left and went down into the lowlands of the Yale making for Stock; but a lane branched right, winding through a wood of ancient oak-trees on its way to Woodhall. ‘That is the way for us,’ said Frodo.

You can take a look at the map in the book and see exactly what he is referring to. But you can also imagine taking a different road and seeing the pleasant countryside sights that the book never describes because the characters simply don’t go that way.

The map itself adds to that because it is drawn in a simpler style than the faux cartographic main maps. You feel that there is a rustic reality to the place that you see on the map, one that you could touch.

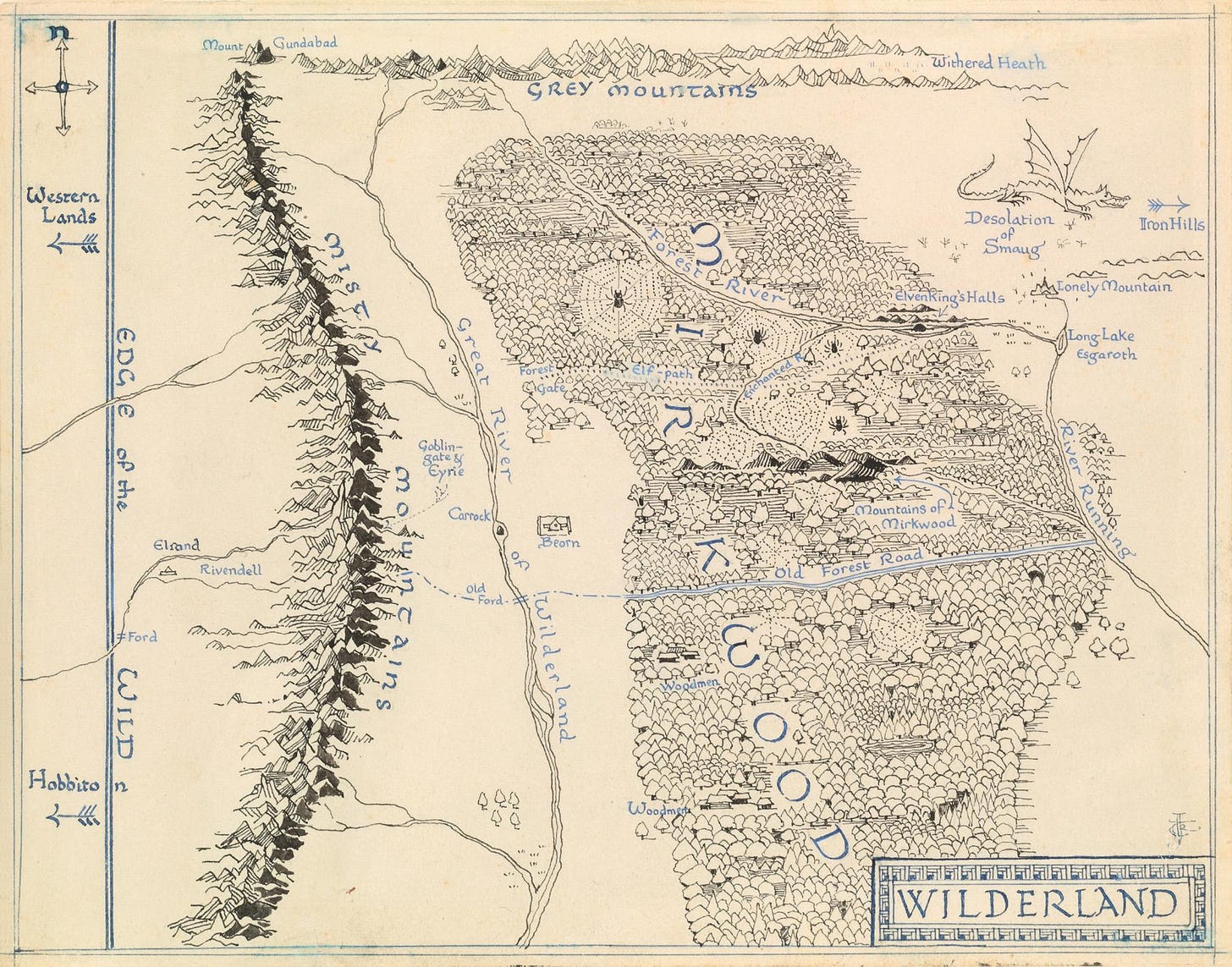

A map that to me gave that feeling and even more is the one that I consider the greatest fantasy map of all: the Wilderland map from The Hobbit.

Looking at the map shows you why. It is not a traditional map by any sense. It is practically an illustration. It’s very similar to what you see when you use the 3D tool in Google World—a view of the ground from an angle, catching the various features of the world in three-quarters profile from above.

And that includes the trees.

The LOTR maps also show trees on them. But they are small and far away and mostly show them from above, a god’s-eye view. In the Wilderland map, you see the trunks of many of the trees, which are larger and more distinct—and you can imagine sitting under them.

The map is not an attempt at total realism or a photographic view. Houses are two-dimensional icons, as are the great spiders in Mirkwood Forest. But the trees bring it all alive and give it a sense of depth.

For the book, that map gives a basic idea of how the travels of Thorin and Company went. But the map gives more than that, by making you imagine being down there. And for me, that makes it the best.

Gygax vs. Gandalf

My affinity for that map goes along very well with my general feelings about Tolkien’s books: that they are best when they are travelogues. And both The Hobbit and LOTR are all about travel. The first book is about traveling out to find treasure; the second is about traveling forward toward a quest and running away from something that is following you. The maps sync up with the travel aspect of the books.

All of that is related, I’d say, to why Dungeons and Dragons seemed to steal so much from Tolkien’s books and yet not feel at all the same.

That it stole a lot was clear enough to the rights holders of Tolkien’s work, who sued TSR because of infringement. The original races and monsters in the first edition of D&D were literally all taken directly from Tolkien; only did later additions include Lovecraftian monsters and some not directly from the Tolkien books.

TSR reacted to the lawsuit in a thesauratic manner: hobbits became halflings, ents became treants. It was basically an admission that LOTR had been a template for much of D&D.

And yet, at the same time, it wasn’t.

In Tolkien, exploring is about finding new lands and discovering their inhabitants. Treasure comes as an afterthought, and is almost never due to the main characters fighting with anyone.

In D&D, especially the first editions and the scenarios that were written for it, exploring is all about finding treasure, avoiding traps, and killing the beasties, monsters, and humanoids that are in your way.

Subsequent versions of D&D and other tabletop roleplaying games added more storytelling and wonder to the hacking and slashing. (I recommend the TTRPG Quest as a good one for playing with kids. It’s available here: https://www.adventure.game/) But the original D&D was all hack and slash.

Part of that is because D&D evolved from wargames that Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson, the cofounders of D&D, had been heavily involved with before they slowly created D&D. In fact, the first “theft” of Tolkien’s work by Gygax had been for his wargame Chainmail. In the fantasy supplement to the game, he described how to have battles between armies of men, orcs, ents, elves, hobbits and so forth. That game was all about the fighting—and D&D was originally subtitled “Rules for Fantastic Medieval Wargames Campaigns Playable with Paper and Pencil and Miniature Figures.”

But it was also because of the kind of fantasy that Gygax was a fan of—and he was no fan of LOTR. He took the elements of Tolkien’s work and used them, at the height of a Tolkien resurgence in the 1970s, but when he listed the influences on D&D in the manual, Tolkien’s name was not there.

In interviews over decades, Gygax expressed his dislike for Tolkien’s work and his boredom with it. The complaints are pretty repetitive. The wizards in Tolkien are underpowered and useless. The fighting men aren’t tough enough. And physically weak characters like hobbits are the heroes.

Which authors had inspired him? Gygax’s main list was Robert E. Howard, L. Sprague DeCamp, and Fritz Leiber. Poul Anderson’s book Three Hearts and Three Lions is one that was also a strong influence, as Gygax said and as has been detailed in Jon Peterson’s history of D&D, Playing the World.

Tolkien’s hobbits rest under trees and eat lunch and look at their surroundings. Try imagining Howard’s Conan the Barbarian doing that. Gygax liked the power fantasies of the sword-and-sorcery books. Travelogues about gentle people in strange lands were not something he aspired to. Sitting under trees is a way of powering up for more killing in Gygax’s fantastical world.

(In one interview, he even throws shade at Tolkien’s ranger Aragorn, which seems odd. Why Leiber’s rogues Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser were really different in his eyes is hard to know.)

Interestingly, aficionados say that the TTRPG that best captures the feeling of Tolkien's books is The One Ring, an RPG set in Middle Earth. One of the main things that makes its system stand out from D&D is that it has a more sophisticated travel mechanic. (Original D&D actually had no travel mechanic and referred you to an Avalon Hill game.) Another thing that makes it stand out is that it deemphasized combat.

Tolkien’s work certainly stands in a different subgenre of fantasy than the sword-and-sorcery books. Much of it is what I’d refer to as “cozy fantasy,” a term I’ll discuss in a future newsletter. And in that vein, the map of Wilderland, though it contains gigantic spiders and dragons and orc holes, is a place to live and perhaps rest under a tree.

*

*

*

As an addendum to an earlier newsletter about showing convincing travel in a fantasy world, I’ll just note that the new Amazon series The Wheel of Time does that well. I think that the technique used is even simpler than the ones I discussed in that newsletter. They simply repeatedly used real locations for multiple closeup and landscape scenes, so that the characters seem to be traveling through an actual place.

There are scenes in which they enter a specific area, closeup scenes with the characters interacting with that landscape as a background, and then scenes later with the characters moving further forward through that same landscape.

Peter Jackson’s LOTR movies occasionally have a scene with some landscape shots and then some closeup action in the same area. But they never have new scenes with the same landscape. So they jump from place to place with no sense of real movement.

Oh, but that Earthsea map brings back a lot of feelings. Thanks for the inside peek at what you find so enchanting about travel books. :)