The book that is a world

Have I reached the end of my most quixotic search?

House of Leaves, S., Pale Fire and others vs. Symbaroum Core Book, Enemy in Shadows, and others

Ever meet someone who just can’t stop talking about a topic, over and over? If you’ve met me, then you have.

There are plenty of topics that fall into that category for me. But one that kept recurring over a period of about ten years was my search for the book that is a world. That sounds crazy, but it’s actually not quite crazy. I think.

The idea that I had in my head was that some books—and I was mostly thinking of fiction—function not just as linear stories but also as nonlinear spaces that you can move forward and backward in. I don’t remember where I first got the idea, but David Foster Wallace’s books, particularly Infinite Jest (which I was never a fan of), may have solidified my thoughts on that.

In Infinite Jest, the chapters are not in a chronological order, though you don’t know that without some serious study of the book. The book also has incredibly long endnotes that are longer than chapters themselves. There’s a certain postmodern pretentiousness going on in the book, but the way you need to jump back and forth and try to figure out earlier chapters based on later information and so forth means that the book functions like a little landscape that you wander around.

Another book that may have sparked that for me was A Visit from the Goon Squad. In some ways, that book is almost just a collection of short stories. But Jennifer Egan also quietly placed some information that illuminates earlier chapters in later chapters, in a way that makes you turn back to better understand what happened before (or after, since the chapters aren’t in chronological order in that book, either).

I may also have been coming from books I read even earlier. Digest books of information, like kids’ encyclopedias, could have you turning back and forth.

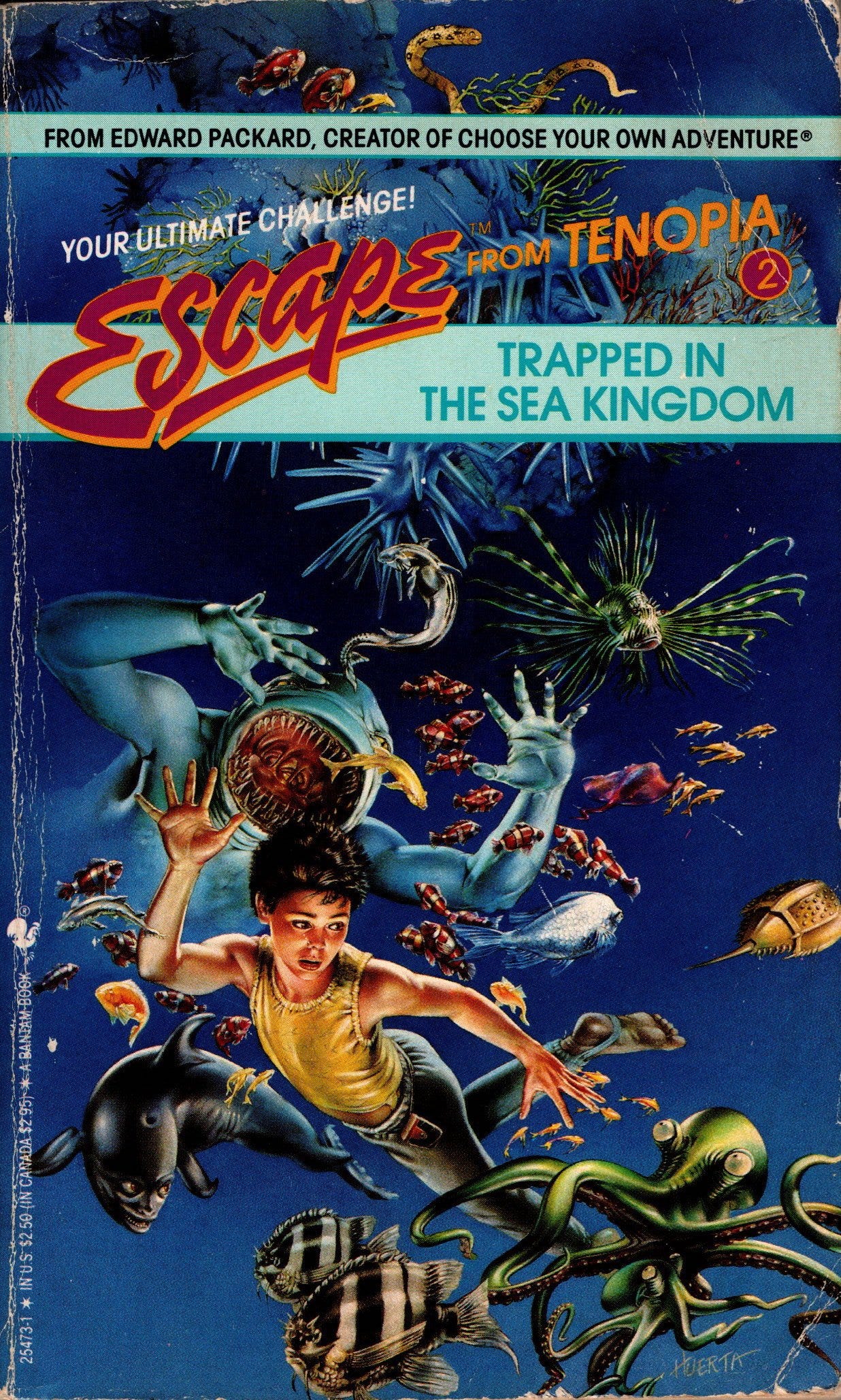

Also, the kids’ series Escape from Tenopia and Escape from the Kingdom of Frome, which I'd read some of as a kid, were influential on my thinking. They were kind of like Choose Your Own Adventure books (and were developed by the same guy who made those), but they were different in a way. Whereas in a CYOA book you followed a basically linear story till the end, whatever path through the book you chose, the Escape books weren’t linear in that way. Their premise was that you were trying to get out of some environment (an undersea section or a castle or a forest), and you might go back through some sections multiple times as you wandered around the environment. Some areas of the book's world became different the second time you went through them. Those books were really like little worlds.

And all of these things led to my obsession: find the book that would really be its own little world.

It’s not that easy.

Literature, I say

The first place that many people would say to look is to more experimental literary fiction of various sorts, and that’s where I headed.

One phrase that repeatedly came up was “ergodic literature.” The academic Espen Aarseth, who apparently coined the term, defined ergodic literature as literature in which a “nontrivial effort is required to allow the reader to traverse the text.” That’s basically the kind of back and forth process that I described above in regard to Infinite Jest.

There are some famous examples. One of the most blatant examples is the book Hopscotch (the original Spanish title is Rayuela) by Argentinean writer Julio Cortázar. In the beginning of the book, an introduction gives two different sequences in which the chapters of the book can be read, to provide different narratives.

Other books often get mentioned in connection with the term ergodic literature, though how well they fit with the original idea varies. But many of them were at least good candidates for my idea, of a book that is a world.

There is Pale Fire, by Vladimir Nabokov. That book revolves around a single poem, and contains a foreword, the text of the poem, lengthy commentary in endnotes, and an index. The fictional editor of the book is a clearly deranged émigré from a fictional Eastern European country who has obviously altered some of the (fictionally) eminent author’s poem. By jumping back and forth between the poem and the endnotes, the reader uncovers the story of the editor—to whatever extent that is possible with an unreliable narrator. And using the index actually uncovers even more, perhaps revealing the real secrets of the story.

Another one that gets mentioned frequently is House of Leaves, by Mark Z. Danielewski. The book’s conceit is that it is an edited version of a discovered manuscript about a film about a family’s experiences in a supernaturally disturbed house. The fictional editor is a drug user whose footnotes begin to show the signs either of heavy drug use or of some sort of possession or haunting as he works on the book. The fictional author of the book was a mysterious blind man. And the film it is supposedly about details a haunting, the details of which are unclear and shifting. The book also contains cartoons, collages, fake transcripts with real people, and a lot of typographic and cryptographic games. Like Pale Fire, it has a weird index that is clearly part of the whole game. I don’t know that the reader really has to jump back and forth in any serious way, however, and House of Leaves, while outwardly seeming to be a great candidate, turned out not to be, after I read through most of it. (I didn’t really enjoy it all that much, either, though I know it has plenty of fans.)

What might seem like the ultimate version of one of these books is the book S., written by Doug Dorst and based on an idea by J. J. Abrams. Though the name of the book is S., what’s actually on its cover, once you remove it from its slipcase, is Ship of Theseus. That book appears to be a library book, with a library sticker on the outside. Open it up, and on pretty much every page of Ship of Theseus are handwritten notes. (Well, of course they’re actually printed, but they look handwritten.) As you look at the notes, it’s clear that they are supposed to be from two different college students, writing to one another, without meeting, about trying to decipher Ship of Theseus, which (in the fictional world of the book in which the college students exist) was written by a mysterious author with possible connections to revolutionary groups.

So not only are you the reader trying to decipher the book Ship of Theseus, you’re trying to decipher what went on between the two students. (It’s clear pretty quickly that they eventually met one another and had a romantic relationship.) There are also various pamphlets, handwritten notes, postcards, and all sorts of other paraphernalia (including a weird code wheel) stuck into the book. You do end up going back and forth, trying to figure out what happened when.

I’ll just say that S. was disappointing to me. The main story of the “actual” book was boring, and I could never figure out how I should read the handwritten notes, after I’d read the entire book or as I read it. Also, many of the mysteries of the book had to do with ciphers and codebreaking, and there are few things that I dislike as much as that.

It didn’t scratch the itch I had.

Rolling up a world

At the end of last year, I was in need of some escapism, and I managed to get myself sucked into the world of tabletop roleplaying games (TTRPGs). In case you’re not sure what that means, the most famous of those is Dungeons & Dragons. I was looking to escape into a fantasy world, and these games gave me a way of actually getting into such a world and wandering around.

These games are basically books. You play them with dice and paper and pencils, as well, and often maps, but the games themselves are written out in books or pamphlets. Generally these books come in three different types: core rulebooks, adventure books, and setting books.

Core rule books are, as their name suggests, books which give the rules of the game. Adventure books give a sort of plot for the game master to present to the players. Setting books present a fictional setting for play to take place in but don’t necessarily present a plot for the game master to follow. Instead, they present a world and its inhabitants, which the game master can use to guide his or her players around.

Some systems have all of these separate. D&D fifth edition, for example, the most popular TTRPG, has its infamous set of three core rule books, the Player’s Handbook, the Monster Manual, and the Dungeonmaster’s Guide. None of these three books really sets out a specific setting for games to take place in. (The DMG does have some descriptions of different planes and levels of hell, but those aren’t really helpful for adventures.)

Instead, you have to buy other books if you don’t want to make up your own adventures or a setting to play in. Since D&D is owned by Hasbro, you can be sure that they know very well how to get players to buy as many of their expensive books as possible.

Other systems put a setting, and perhaps an adventure, in a single book along with the rules. For example, the Swedish fantasy TTRPG Symbaroum goes through some detail in describing its setting in its core book, and then at the end has a couple of introductory adventures to run. For more detailed explorations of the various cities, towns, ruins, and forests in the world of Symbaroum, there are other books. But you can theoretically pick up the core rule book and have an adventure using just the information there.

My argument is that adventure books and particularly setting books are the little worlds in a book that I was looking for. It’s not just that you flip back and forth in the books, rather than reading through them sequentially. It’s that they present a little world in a book that you can actually travel through, by playing the game.

Some of these worlds are immense and complicated. For example, one of the best-loved adventure books is the book Enemy in the Shadows, for the British TTRPG Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay. It’s the first part of a long campaign called Enemy Within, in which you travel around the faux and fantasy version of medieval Germany of Warhammer and contend with the politics of the various cities there and the demonic incursions that lie behind some of the more bizarre political issues.

Enemy in Shadows, like the books in the series that follow it, is full of individual characters to interact with and places to explore. The book is an adventure, so it presents events for the game master to lead the characters through. But it also provides detailed overviews and maps of cities, so a game master and players can play sessions in which they just explore, without following a plot. There’s a large world to wander around inside this book.

There are smaller worlds available, as well. The recent cheap, small TTRPG setting book The Black Wyrm of Brandonsford presents a nice little area for players to wander around. There’s a little village, with funny problems going on between the villagers. There is a dragon in a cave. There is a giant in a house in the woods. There is no plot being presented; the characters can just learn about the world and do what they want. This, too, presents a tiny world in a book.

I’m not sure where my quixotic search came from to begin with. But I do think that in a real way, these books have given me an idea of what I was searching for in the first place.